I had experimented too much, this repo is fully of garbage code that really can't be salvaged.

Please use my other squava repo

Squava is a tic-tac-toe variant. Moves are made like tic-tac-toe, except on a

5x5 grid of cells. Players alternate marking cells, conventionally with X or

O. Four cells of the same mark in a row (verical, horizontal or diagonal)

wins for the player with that mark. Three cells in a row loses. That is, a

player can win outright, or lose.

You can play the JavaScript version right now!

You can play a Monte Carlo Tree Search version right now!

The rules have an ambiguity, in that it isn't clear what to do if a single marker fills in a row of 3, say, and a diagonal of 4. Does that player win or lose?

I chose "win", mainly because it's computationally easier to check for 4-in-a-row as a win separately from 3-in-a-row as a loss. After all, every 4-in-a-row has 3-in-a-row inside it.

Neither player can win until the 7th move (4 for starting play, 3 for the other). The starting player can win on odd-numbered moves by winning with 4-in-a-row. The starting player can lose on even-numbered moves by losing with 3-in-a-row.

Similarly, the second player wins on even-numbered moves by getting 4-in-a-row, or loses on odd-numbered moves with 3-in-a-row.

Peiyan Yang has put together a program that has solved the game for the first player, if that player plays (2, 2).

Command line, text interface. squava (the program) command line options:

-C Computer takes first move

-D Play deterministically

-H Human takes first move (default true)

-M string

Tell computer to make this first move (x,y)

-d int

maximum lookahead depth (default 10)

-n Don't print board, just emit moves

-r Randomize bias scores

-B Computer opens from a "book", first or second move

The multithreaded version adds:

-N Use this many threads (default 4)

The Monte Carlo Tree Search version has these options:

-C Computer takes first move

-i int maximum iterations (default 10000)

-u float UCTK explore/exploit coefficient (default 1)

Alpha-Beta minimax, algorithm

from Wikipedia. Since more than one move can result in the maximum numerical score,

squava keeps a list of all moves that have that maximum numerical score, and chooses

one at random to actually play. The -D flag will skip the choice, and always play

the same move in identical situations.

The lookahead (number of moves ahead the code considers) varies during the game. If less than 8 marks appear on the board, it looks ahead 4 moves (2 moves each for both players). If less than 13 marks appear on the board, it looks ahead 3 moves for each player. If more than 12 marks appear, it looks ahead 5 moves for each player. This is something I set by trial and error. I set the lookahead to as large a number as I could stand to wait for. If the human plays right in the first few moves when the program isn't looking too far ahead, the human can win.

The threaded (goroutined) version has a simple worker pool design. It starts a number of goroutines that block on a buffered channel of pointers-to-game-state. When the program needs to decide on a move, it makes one game-state struct for each possible move it can make. The game-state structs go into the buffered channel. Each worker goroutine gets a game-state struct, does the alpha-beta minimaxing for a single move, and puts the result on another buffered channel. The main goroutine waits for results and chooses the maximum-valued move to play.

The Monte Carlo Tree Search algorithm comes very directly from Python code. The default number of iterations (10000) seems far too small in practice. I find playing it more fun than playing any of the minimaxing versions. Since there's about 177,925,144,320,000 games for the first 11 moves, it's not too surprising that 10,000 iterations is too small.

Every good alpha-beta minimax program has a "book" for the initial moves.

I've included some programs to help build a "book" for squava:

opening2 can perform a very deep valuation of the 6 cells that are unique first moves.

There's 25 empty cells at the start of a game. All but 6 first moves can be generated by rotations

or reflections of the board.

opening3 can perform very deep evaluations of all 6 first moves, and all unique (under rotation

and reflection) response moves. This lets me check which response is best for each opening move.

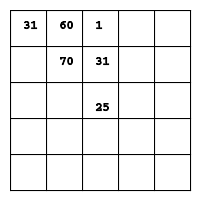

First move values to first player, 14 ply lookahead

I think that the scores get assigned based on the lookahead finding situations like this:

0 1 2 3 4

0 _ _ _ _ _

1 _ O _ X O

2 _ X X _ _

3 _ _ _ _ _

4 _ O _ _ _

The human moved first (using 'O' marks), and moves went like this:

- 1,1

- 2,2

- 1,4

- 1,3

- 4,1

- 2,1

That's a reasonably good opening for 'O'. Depending on how 'X' plays, 'O' can have 3 possible 4-in-a-rows. In this particular game, the computer (playing 'X') predicts it will lose. The first 3 'X' moves put it in a situation where it can't move to (0,4), (3,1), (2,0), (0,4), (2,3) without creating 3-in-a-row and losing.

A diagonal 4-in-a-row for 'O' exists between (4,1) and (1,4). 'X' cannot move to (2,3) without losing. Next move for 'O' should be (3,2). 'X' next move is immaterial, and 'O' wins with (2,3).

Counting reflections, there's 16 triangles like 'O' made above, 4 for each corner of the board. All 3 vertices of the triangles end up on high-valued cells of the first move diagram above.

You can counter your opponent in the early moves of a game to prevent formation of a triangle trap. The computer's static evaluation function doesn't look far enough ahead in the games first 4 moves to avoid getting caught in a triangle in a later phase of the game.

Experimentation leads me to believe that the best first moves are (1,1), (1,3), (3,3) and (3,1). The worst first move is (2,2), the center of the board, followed by (0,2), (1,2), (2,0), (2,1), (2,3), (2,4), (3,2), (4,2).

After reaching its lookahead depth (which varies throughout the game) the code does a static valuation of the board - it assigns a numerical value to the layout of X's and O's. By default, the static value has a slight bias towards moves at the corners of the board, and a slight bias towards winning (or forcing a loss) in as few moves as possible.

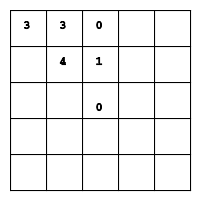

Default bias - reflect to get all cells' bias

Using the -r flag causes the program to give a random bias, from -5 to 5 for each

cell. Using -r can cause the program to vary its opening moves, and give the human

a small advantage.

After the slight biases, it gives larger magnitude scores for having a non-losing any 3 out of a winnning 4-in-a-row combination.

It gives a large negative score for the computer losing by 3-in-a-row, or by human winnning. It gives a large positive score for for computer winning, or human losing by 3-in-a-row.

Experimentally, considering 2-of-loosing-3 does not make a difference in the program's play. I think this is because every winning 4-in-a-row stems from a losing 3-in-a-row created two moves before.

There are some configurations it should avoid, but doesn't. Two adjacent marks

flanked by empty cells means that player cannot play either of the empty cells

without losing. Only squavathr, the multi-threaded version, takes this

into account.

Other than tic-tac-toe, where it's feasible to check the entire game tree on every move, this is the first static valuation function I've written that actually produces a worthwhile opponent, and it's also quite simple.

go build squava.go

go build squavathr.go # Multi-goroutine version

go build sns.go # NegaScout

go build playoff5.go

go build squavam.go # Monte Carlo Tree Search

go build squavam2.go # Multi-threaded Monte Carlo Tree Search

squava will execute an Alpha-Beta minimax search for the best move. sns

will execute a

NegaScout search.

squavam does a Monte Carlo Tree Search to probably find the best move.

sns, squava, squavathr and squavam behave mostly identically.

$ ./squava

Your move:

to have the computer use a "book" opening:

$ ./squava -B

Using opening book

My move: 1 1

0 1 2 3 4

0 _ _ _ _ _

1 _ X _ _ _

2 _ _ _ _ _

3 _ _ _ _ _

4 _ _ _ _ _

You enter 2 digits in the range 0 to 4, with a space or spaces between them. The computer ponders, announces its move, and displays the board. Human plays 'O', computer plays 'X'.

You can have the computer go first:

./sns -C

My move: 0 0 (30) [2800381]

0 1 2 3 4

0 X _ _ _ _

1 _ _ _ _ _

2 _ _ _ _ _

3 _ _ _ _ _

4 _ _ _ _ _

Your move:

sns chose the cell at <0,0>, which had a value of 30, and visited 2,800,381 leaf nodes

of the game tree to arrive at that move.

You can force the computer to choose a particular opening move:

./squava -M 1,1

My move: 1 1

0 1 2 3 4

0 _ _ _ _ _

1 _ X _ _ _

2 _ _ _ _ _

3 _ _ _ _ _

4 _ _ _ _ _

I find that a typical game has two phases: opening, where there's up to 5 pieces on the board. A midgame, where you try to win by getting 4-in-a-row, while keeping the computer from getting 4-in-a-row. Rarely, you can get to a third phase, an end game, where no 4-in-a-row is possible, and the goal becomes to avoid losing by being forced into 3-in-a-row.

You can see the end game taking place by running two instances of squava in

two xterms. Start one as ./squava -C. It will chose a move first. Type

that move into the second instance, which expects the "human" to move first.

25-move games are possible. As near as I can tell 'O' (second player) always wins those full-board games. I don't have a proof for this yet.

The playoff5 program allows you to run instances of two algorithms against

each other:

$ ./playoff5 -1 A -2 N

AlphaBeta <3,3> (18) [95864]

NegaScout <4,0> (5) [4134847]

0 1 2 3 4

0 _ _ _ _ _

1 _ _ _ _ _

2 _ _ _ _ _

3 _ _ _ X _

4 O _ _ _ _

AlphaBeta <3,1> (99) [184528]

NegaScout <2,4> (30) [1377241]

0 1 2 3 4

0 _ _ _ _ _

1 _ _ _ _ _

2 _ _ _ _ O

3 _ X _ X _

4 O _ _ _ _

...

The AlphaBeta instance almost always wins. You can play off two of the same algorithm, or order them differently:

$ ./playoff5 -1 N -2 A

NegaScout <3,2> (30) [2800381]

AlphaBeta <2,1> (-8) [405536]

0 1 2 3 4

0 _ _ _ _ _

1 _ _ _ _ _

2 _ O _ _ _

3 _ _ X _ _

4 _ _ _ _ _

...

You can select the players' algorithms.

You specify what the first player by -1 x, and the second player by -2 x.

- 'A' for an alpha/beta minimaxing player

- 'N' for a Negascout minimaxing player

- 'B' for an alpha/beta minimaxing player that has an opening for its first 3 moves.

- 'G' for an alpha/beta minimaxing player that tries to stay out of bad positions

- 'M' for a Monte Carlo Tree Search version, 150,000 iterations

Point-n-click, runs in your browser. Single HTML file.

JavaScript transliteration of an earlier version of the Golang version.

Apparently Squava was invented by Néstor Romeral Andrés